- Home

- Samuel Sykes

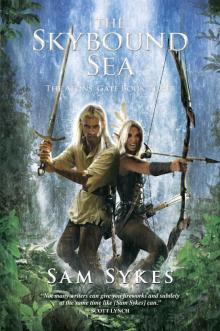

The Skybound Sea Page 5

The Skybound Sea Read online

Page 5

“And I will not watch you languish in their—” he thrust a finger toward the door, “—company. I will not watch you die with no one but criminal scum to look on helplessly as they wait for the last breath to leave you before they can rifle your body and feed it to the sharks.” He inhaled deeply, regaining some composure. “Coarse as it may seem, this is protocol for a reason, Dreadaeleon. Whatever else the Venarium might do once the Decay claims your body, we are your people. We know how to take care of you in your final days.”

Dreadaeleon said nothing, staring down at his arm. It began to tremble once more. He focused to keep it down.

“When do we leave, then?”

“By the end of today,” Bralston replied. “As soon as I conclude business on the island.”

“With whom? The Venarium has no sway out in the Reaching Isles.”

“The Venarium holds sway anywhere there is a heretic. Even if Sheraptus is gone, we are duty-bound to make certain that none of his taint remains.”

“Lenk agrees with you,” Dreadaeleon said, sighing. “That’s why he’s had Denaos on interrogation duty.”

“Denaos …” Bralston whispered the name more softly than he would whisper death’s. “Where is he conducting this … interrogation?”

“In another hut at the edge of the village,” Dreadaeleon replied. “But he doesn’t want to be—”

He looked up. Bralston was gone. And he was alone.

THREE

THE ETIQUETTE OF BLOODSHED

It always seemed to begin with fire.

As it had begun in Steadbrook, that village he once called home that no one had ever heard of and no one ever would. Fire had been there, where it had all begun. Fire was still there, years later, every time Lenk closed his eyes.

It licked at him now as it consumed the barns and houses around him, as it sampled the slow-roasted dead before giving away all pretenses of being civilized and messily devoured skin, cloth, and wood in great red gulps. It belched, cackled at its own crudeness, and reached out to him with sputtering hands. The fire wanted him to join them; in feast or in frolic, it didn’t matter.

Lenk was concerned with the dead.

He walked among them, saw faces staring up at him. Man. Woman. Old man’s beard charred black and skin crackling. Through smoke-covered mirrors, they looked like him. He didn’t remember their names.

He looked up, found that the night sky had moved too fast and the earth was hurrying to keep up. He was far away from Steadbrook now, that world left on another earth smoldered black. Wood was under his feet now, smoldering with the same fire that razed the mast overhead. A ship. A memory.

A different kind of fire.

This one didn’t care about him. This fire ate in resentful silence, consuming sail and wood and dying in the water rising up beneath him. Again, Lenk paid no attention. He was again concerned with the faces, the faces that meant something to him.

The faces of the traitors.

Denaos, dark-eyed; Asper, sullen; Dreadaeleon, arrogant; Gariath, inhuman. They loomed out of the fire at him. They didn’t ask him if he was hot. He was rather cold, in fact, as cold as the sword that had appeared in his hand. They didn’t ask him about that, either. They turned away, one by one. They showed their necks to him.

And he cut them down, one by one, until one face remained.

Kataria.

Green-eyed.

Full of treason.

She didn’t show him her neck. He couldn’t very well cut her head off when she was looking right at him. His eyes stared into her.

Blue eyes.

Full of hate.

It was his eyes she stared into. It wasn’t his hands that wrapped themselves around her throat. It wasn’t his voice that said this was right. It wasn’t his blood that flowed into his fingers, caused his bones to shiver as they strained to warm themselves in her throat.

But these were his eyes, her eyes. As the world burned down around them and sank into a callous sea, their eyes were full of each other.

He shut his eyes. When he opened them again, he was far below the sea. A fish, bloated and spiny and glassy-eyed stared at him, fins wafting gently as it bobbed up and down in front of him.

“So, anyway,” he said, “that’s basically how it all happened.”

The fish reared back, seeming to take umbrage at his breaking of the tranquil silence. It turned indignantly and sped away, disappearing into the curtains of life emerging from the reef.

“Rude.”

“Well, what did you expect?”

He turned and the woman was seated upon a sphere of wrinkled coral. Her head was tilted toward him.

“I am talking and breathing while several feet underwater.”

“You don’t seem surprised by that,” she said.

“This sort of thing happens to me a lot.” He tapped his brow. “The voices in my head tend to change things. It didn’t seem all that unreasonable that they might make me talk with a fish.” He looked at her intently. “You should know all this, shouldn’t you?”

“Why would I?”

“Can’t you read my thoughts?”

“Not exactly.”

“All the other ones have been able to.”

“I’m not a voice in your head,” she replied.

Amongst everything else in … whatever this was, that was the most believable. Her voice came from the water, in the cold current that existed solely between them. It swirled around him, through him, everywhere but within him.

“What are you, then?” he asked.

“I am just like you.”

“Not just like me.”

“Well, no, obviously. I don’t want to murder my friends.”

“You said you couldn’t—”

“I didn’t, you showed me.” She leapt off the coral, scattering a school of red fish as she landed neatly. A cloud of sand rose, drifted away on a current that would not touch her. “And before that, you told me.”

“When?”

“When you cried out,” she said, turning to walk away. “I’ve been hearing you for a while now. There aren’t a lot of voices anymore, so I hear the few that scream pretty clearly.”

As she walked farther away, the sea became intolerably warm. The cold current followed her and so did he. He didn’t see when she stopped beside the craggy coral, and he had to skid to a halt. She didn’t even look up at him as she peered into a black hole within the coral.

“Voices?”

“Two of them,” she said, reaching into the black hole. “Always two of them. One in pain, one always crying out, one weeping bitterly and always saying ‘no, no, no.’ That is the voice I follow. That is the one that’s faint.”

She winced as a tremor ran along her arm. She withdrew it and the eel that had clamped its jaws onto her fingers. It writhed angrily as she brought her hand about its slender neck and brought it up to her face to stare into its white eyes.

“And the other?” Lenk asked.

“Always louder, always cold and black. It doesn’t speak to me so much as speak to mine, speak to the cold inside of me.”

He stared at her, the question forming on his tongue, even though he already knew the answer. He had to ask. He had to hear her say it.

“What does it tell you to do?” he asked.

She looked at him. Her fingers clenched. The snapping sound was short. The eel hung limply in her hands, its tail curled up, up, seeking the sun as she clenched its lifeless body.

“To kill,” she said simply.

Their eyes met each other, peering deeper than eyes had a right to. It was as if each one sought to pry open the other’s head and peer inside and see what each one’s frigid voice was muttering to them.

He could feel the cold creeping up his spine. He knew what his was telling him.

“So,” he said softly, reaching for a sword that wasn’t there, “you’re here to—”

“Kill you?” Her smile was not warm. “No.” She released the eel and let

it drift away. “It’s not in my nature.”

He rubbed his head. “I don’t mean to be rude, but this is about the time I start losing patience with the other voices in my head, too, so could you kindly tell me why you are here?”

“Because, Lenk, you’re about to kill yourself.”

“The thought had occurred. I’m just worried that hell will be much worse than …” He gestured around the reef. “You know, this.”

“What makes you so sure there’s a hell?”

“Because I’ve seen what comes out of it.”

“Demons aren’t made in hell. They’re made by hell.” She leveled a finger at him. “The kind of hell that you’re going through.”

“I don’t—”

“You do.” She spoke cold, sharp, with enough force to send the fish swirling into hiding. Color died, leaving grim, gray corals and endless blue. “You hear it every time you think you’re alone, you see it every time you close your eyes. You feel it in your blood, you feel it sharing your body. It never talks loud enough for others to hear, but it deafens you, and if they could hear what it says, you know they’d cry out like you do.

“Kill. Kill,” she hissed. “You obey. Just to make it stop. But no matter how much your sword drinks, it will never be enough.” She narrowed her eyes at him. “If you kill them, Lenk, if you kill her, it still won’t be enough.”

Her voice echoed through water, through his blood. She wasn’t just talking to him. Something else had heard her.

And it tried to numb him, reaching out to cool his blood and turn his bones to ice. It only made the chill of her voice all the more keen, made the warmth of the ocean grow ever more intolerable. He wanted to cry out, he wanted to collapse, he wanted to let go and see if the current could carry him far enough that he might drift forever.

Those were not things he could do. Not anymore. So he inclined his head, just enough to avoid her gaze, and whispered.

“Yeah. That makes sense.”

“Then you know?” she asked. “Do you know how to fight it? That you have to fight it?”

Her voice was hard, but falsely so, something that had been brittle to begin with and hammered with a mallet in an awkward grip. Not hard enough to squelch the hope in her voice. She asked not for his sake alone.

He hated to answer.

“I’m not afraid of it, anymore.”

He tilted his head back up, turning his gaze skyward. The sun was distant, a shimmering blur on a surface so far away as to be mythical.

“I used to be,” he said. “But it says so many things. I tried ignoring it and I felt fear. I tried arguing and I felt pain. But now, I’m not afraid. I don’t hurt. I’m numb.”

“If you can safely ignore it, then is there a problem? If you don’t feel the need to kill—”

“I do.” He spoke with a casualness that unnerved himself. “The voice, when it speaks, tells me about how they abandoned me, how they betrayed me. It tells me they have to die for us to be safe. I try to ignore it … but it’s hard.”

“You said you were numb, that you weren’t afraid.”

“It’s not the voice that scares me.” He met her gaze now. He smiled faintly. “It’s that I’m beginning to agree with it.”

Denaos looked at himself in the blade. No scars, still. More wrinkles than there used to be. A pair of ugly bags under eyes that he chose not to look at, but no scars.

He had that, at least.

Appearance was one point of pride amongst many for him. There were other things he had hoped he would be remembered for: his taste in wine, an ear for song, and a way with women that sat firmly between the realms of poetry and witchcraft.

And killing, his conscience piped up. Don’t forget killing.

And killing. He was not bad at it.

Still, he thought as he surveyed himself, if none of those could be his legacy, looks would have to suffice.

And yet, as he saw the man in the blade, he wondered if perhaps he might have to discount that, too. His was a face used to masks: sharp, perceptive eyes over a malleable mouth ready to smile, frown, or spit curses as needed, all set within firm, square features.

Those eyes were sunken now, dark seeds buried in dark soil, hidden under long hair poorly kempt. His features were caked with stubble, grime, a dried glistening of liquid he hadn’t bothered to clean away. And his mouth twitched, not quite sure what it was supposed to do.

Fitting. He didn’t know who this mask was supposed to portray.

Looks, then, were not to be what he was remembered for. His eyes drifted to the far side of the table, to the bottle long drained. His preferences in alcohol, too, had broadened to “anything short of embalming fluid, providing nothing else is at hand; past that, it’s all fine.”

He would not be remembered as a handsome man, then. Nor a man of liquids or songs. What else was left?

The glistening of steel answered. He looked at the blade, its edge everything he wasn’t: sharpened, honed, precise. An example, three fingers long and with a polished wooden hilt and a taste for blood.

Killing, then.

“Are we doing this or what?” a growling voice asked.

That, he thought, and a way with women.

He tilted the knife slightly. She was still there. He had hoped she wouldn’t be, though that might have been hard, given that she was bound to the chair. Still, less hard considering what she was.

Indeed, it was difficult to see how Semnein Xhai was still held by the rawhide bonds. They might have bit into her purple flesh, they might have been tied tightly by hands that were used to tying. Her arm might have been twisted and ruined, thanks to Asper. But that purple flesh was thick over thicker muscle, and his hands were shakier these days.

She stared at him in the blade, her eyes white and without pupils. Her hair hung about her in greasy white strands, framing a face that was sharp and long as the knife.

And looking oddly impatient, he thought. Odder still, given that she knew full well what he could do with this. The scar on her collarbone attested to that. The fresh cut beneath her ribcage, shallow and hesitant, gave a less enthusiastic review.

He had been wearing a different mask that day, that of a man who had a better legacy than him, a man who was less good at killing. But he would do better today. He had people counting on him to find out information. That was a slightly better legacy.

Still killing, though, his conscience said. Or did you think you were going to let her go after she told you what you wanted to know? Pardon, if she tells you.

Not now, he replied. People are counting on me.

Right, right. Terribly sorry. Shall we?

His face changed in the blade. His mask came back on. Dark eyes hard, jaw set tightly, twitching mouth stilled for now. Hands steadied themselves. He smiled into the blade: knife-cruel, knife-long.

Let’s.

He held up the knife and regarded her through the reflection of its steel. Glass was fickle. Steel had a hard time lying. He knew what he was doing. He knew this should have been easier than it was.

One look into her long, purple face reminded him why it wasn’t. No fear in her reflection. Fear would have been easy to use. Contempt, too, would have been nice. Lust would have been passable, if weird. But what was on her was something hard as the rest of her, something impatient and unimpressed.

That was hard to work with. That hadn’t gotten any easier.

Not impossible, though.

“And?” she grunted. “Any more questions today?”

“No,” he replied, voice as soft as the sunlight filtering through the reed walls. “I want to tell fairy tales today.”

No reply. No confusion or derision. She was listening.

She was also fifteen paces behind him.

“Old ones, good ones,” he whispered. “I want to tell the stories that mothers make crying children silent with. Handsome princes—” he paused, turned the blade, stared into his own eyes, “—ugly witches—” he ran his finger al

ong the blade, felt it gently lick his flesh, “—pretty, pale princesses with long, silky hair.”

He shifted the blade, looked at her again. Three paces to the left.

“Was a quiet child,” he continued without turning around. “Mother didn’t tell me stories. Never cried. I had a friend, though, cried a lot. Probably why he didn’t think he was too old for fairy tales. Made him cry once … twice, maybe. Heard his mother tell him stories. All the same: evil witch captures pretty princess, handsome prince rides to tower. The ending …”

He shifted the blade to his left hand. He stared at her for a moment longer in its reflection.

“It’s always the same.”

His arm snapped. The knife wailed. It quieted with a meaty smacking sound and her shriek of pain. He turned, smiled gently.

“There is a struggle, some brave test for the prince to conquer,” he whispered as he walked over to her. “But in the end, he reaches the top of the tower—” he took the hilt jutting from her bicep, “—he kicks in the door—” he twisted the blade slightly, ignored her snarling, “—and he carries the pretty princess out.”

He drew the blade out slowly, listening to it whine as it was torn from its nice, cozy tower, listening to the flesh protest. He caught his reflection in the steel, saw that his smile had disappeared.

“Always the same,” he said. “The fairy tale is how we tell ugly children to survive. This is why the same stories are told. Through repetition, the child understands.”

He lifted the blade, tapped it lightly on her nose, leaving a tiny red blot upon her purple flesh.

“And we can repeat this story forever.” He slowly slid the blade over, until the tip hovered beneath her eye, a hair’s width from soft, white matter. “The princess can keep going back into the tower until you tell me. Until I know where Jaga is and what you handsome princes want with it.”

Now, he waited. He waited for the fear to creep up on her face. He waited for something he could use. He waited until she finally spoke.

“I have to piss.”

He sighed; mistake. “Just let me—”

She wasn’t making a request. The acrid smell that hit him a moment later confirmed that. He blanched, turned around; bigger mistake.

The Skybound Sea

The Skybound Sea